Designers are accustomed to receiving briefs in various forms, from concise stories to lengthy design requests. A seasoned designer adeptly navigates through these inputs, which serve as guides for exploration and set boundaries. However, sometimes, these inputs unintentionally hinder the success of a product by restricting a designer's ability to make meaningful contributions.

We believe that—regardless of the format of input from Product, Business, or Executives—a brief should adhere to a simple rule: make sure that the brief itself doesn't inadvertently dictate or limit the quality of the design output. This article explores how this can happen, why it’s so common, and ways Designers can proactively manage it. (And while this article is really written for Design Leaders, to help make their teams happier or more productive, Designers as well as Product Managers could start using some of these ideas today.)

As a design consultancy, our clients range from startups to large enterprises, involving individuals from newly appointed Product Managers to VPs of Product and CTOs. You can imagine that what we receive when we start working on a project varies WIDELY, from face-to-face discussions to detailed product requirements documents (PRDs) or design briefs in various forms.

We have a lot of practice making sure we can add as much value as possible and we’ve developed a theory about the key to doing so…

How do inputs affect outputs?

Sometimes Designers take the fidelity of the input (the brief) to be an indicator of what they’re supposed to output. A Product Manager might create a mockup in PowerPoint because they have an idea in their head about how something might work. (Humorous aside — an anonymous friend at Figma told me that one popular theory there is that the #1 tool for producing mockups in the industry is PowerPoint!).

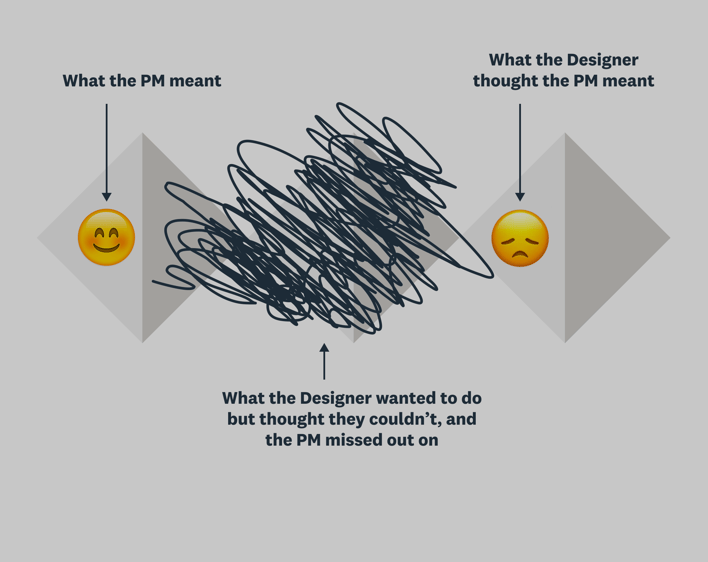

The Designer receives a mockup and thinks, “Oh, this is close to done, I just need to pretty it up a bit.” In reality, that might be completely wrong—the PM is thinking “Here is one idea, I assume you’ll come up with others if it’s not the best,” or even, “I hate writing, I’m just going to try to explain what we’re trying to accomplish with a picture, but I don’t care if it ends up looking like this at all.”

Yikes. That PM and that Designer are in totally different places! What’s an easy way to talk through where we are in the process and what we’re trying to do now?

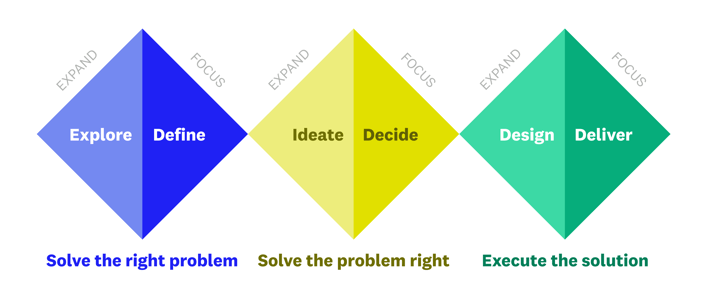

Many Product Managers and most Designers are familiar with the double- or triple-diamond design process diagram:

In each phase of this process, we’re interested in answering certain questions, and we expect to produce certain kinds of artifacts.

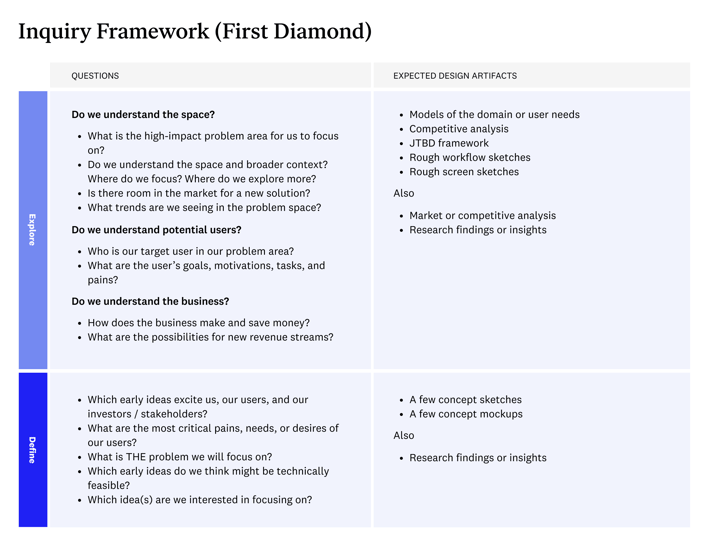

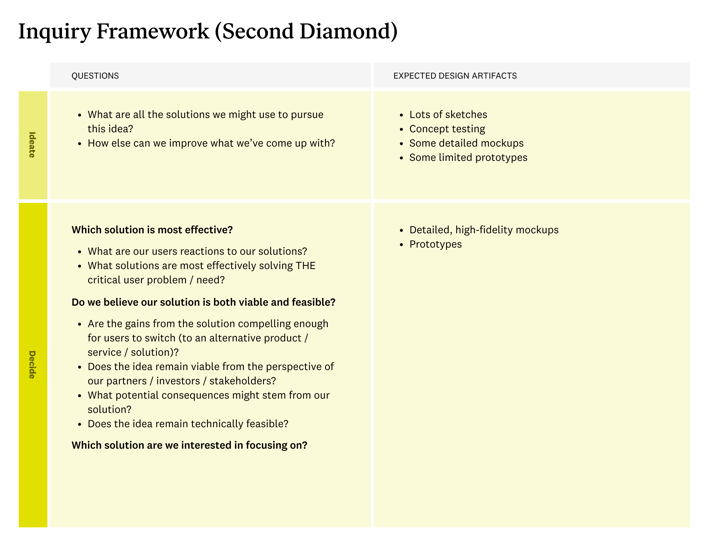

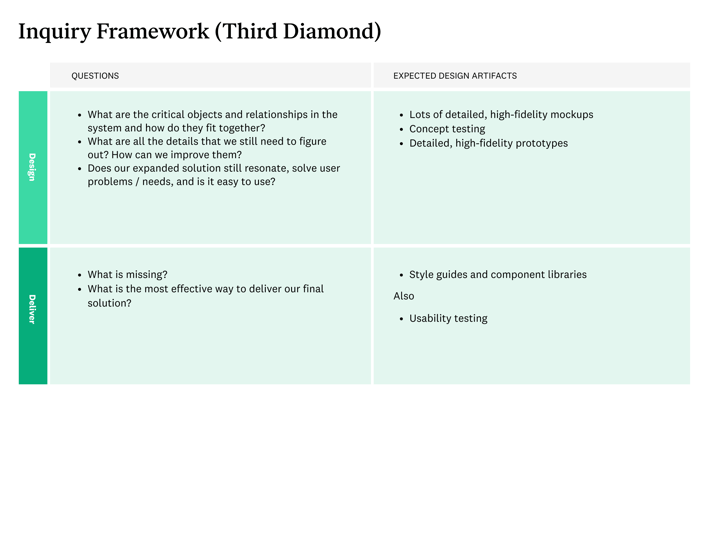

Some examples of those questions and artifacts (and note that I'm not claiming this list is exhaustive or perfect!):

Differentiating between concepts and details

Now, can you tell the difference between a concept mockup and a detailed, high-fidelity mockup? I’ve been in this business for (mumble, mumble) years and I’ll tell you, I can not. Sometimes I can tell where we are in the process by the number of artifacts that have been produced, but not always.

It all depends on various factors:

- the designer, their time, skill and speed

- what’s extant; does this live in a product where nav and design system is already done, or from scratch?

- the rest of the team; are they doing design by committee or providing detailed feedback on the earliest of mockups?

We have to be explicit about where we are in the process, what’s known and what’s not. Because when there is a mismatch between the artifact(s) in the design brief and the questions we’re exploring, we limit the impact of the Designer’s contribution, and ultimately limit the outcome of the collaboration.

In the example I gave above, there is a PowerPoint mockup included in the design brief. Unless the PM specifically states otherwise, Designers can easily take this as an indicator that the PM is basically saying, “I’m pretty far along in the process (e.g., in the 4th triangle, Decide). I understand the problem and am confident in the solution, and I just need you to help work out the details (do the 5th triangle, Design).”

When in fact, the PM might be saying “I have an idea about how to address the need we’ve identified,” (2nd triangle: Define) and they actually really want to explore other ways to do it. (Still 2nd triangle.)

Then what happens?

- The Designer is frustrated about being brought in so late in the process, because the artifact implies the fourth triangle. Designers often hate being asked to make a fully-baked solution “look pretty”. It’s the subject of an oft-requested talk I give about getting a “napkin sketch”.

- The Product Manager is frustrated that all the Designer is contributing is adding details and making stuff look pretty — or worse, the Product Manager thinks that this is all a Designer is capable of and that, in the future, that’s all they can expect.

- …and the actual work suffers, because the team isn’t working together to build on what they know, to develop and improve ideas, or to ask and seek answers to their questions.

A good analogy here is imagine you've picked up paint chips from the hardware store and are showing it to your roommate/partner. The paint chip is an artifact or idea. You still need to be clear on what you’re saying:

- Is it an irrefutable fact? (e.g. “I’m moving out if we don’t do something about the living room,” or, “I love this color and I will die without it.”)

- Is it a question? (e.g. “I wonder if you think this yellow color would make it more cheery in here?” or, “Do you have any ideas about how we could brighten up the living room?”)

- Is it a specific request? (e.g. “Pick up a gallon of this paint, please.”)

- Is it some combination?

How can we manage the bad input / limited output affect?

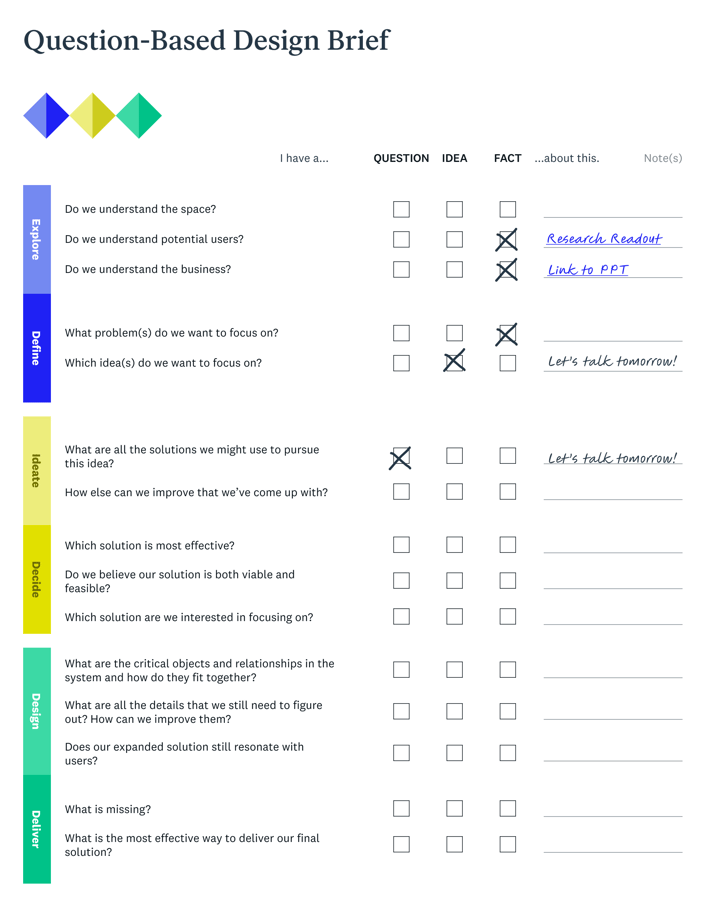

To mitigate the negative effects of poorly defined input, we propose PMs and Designers work together to explicitly separate FACTS, IDEAS, and QUESTIONS in a design brief.

- Here are the FACTS; what I know for sure.

- Here are my IDEAS; what I’ve thought about so far.

- Here are the QUESTIONS; what I want to explore or need from you.

Artifacts, like the high-fidelity mockup described above, are just ideas most of the time (but, sneakily, not all of the time!).

When a design brief is unintentionally limiting, it’s because the IDEAS are in the form of an artifact that implies a certain set of FACTS and a certain kind of QUESTION to explore, but the team isn’t explicit and just rolls with whatever was implied.

Better briefs in practice

At DesignMap, our Designers start by asking Product Managers to clarify what’s a FACT, what’s a QUESTION, and what’s an IDEA. Designers can start by using the table above to run through the questions with the PM to identify where you are in the process. Then, specifically ask about any wireframes or mockups: Is this a FACT or is it an IDEA?

A detailed mockup (IDEA) might be totally appropriate if the PM needs your help with figuring out the details (QUESTION) because the FACT is that there is a real deadline in two weeks and there isn’t time for exploration.

On the other hand, detailed mockups (IDEA) can also be appropriate if the PM wants to explore lots of other ways to solve the problem (QUESTION) as long as the team is explicit and clear that’s what we’re doing.

We realize this is a lot to follow, which is why we’ve created this downloadable worksheet (here in Google Slides or here via Figma) to serve as the cover sheet of any design brief or as a collaborative exercise to fill it out together as the first step in your process. We recommend going through the form together, but even async is better than not at all!

A parenthetical: At DesignMap we've had the experience of PMs saying they are open to exploring something when, in fact, they’re really attached to their idea and not open to others. Not, it’s not just you!

I understand that sometimes PMs may not realize how attached they are until you start looking at other ideas, but hopefully you can have an open, realistic conversation up front so that the team isn’t hung up later trying to do something that really isn’t wanted 🙂. And, if as a Designer, you thought you had that conversation but all your ideas are being rejected, it might be worth going back to the list of questions and reiterating where you are in the process and what you are expected/expecting to contribute.

A "Perfect" Conversation

Let’s go beyond the theory of this and look at how it might actually happen in the wild — because it’s really the details in the conversation that help develop understanding and elevate the work.

Imagine a SaaS company, where a Product Manager and Designer are assigned to work on a project together…

The Product Manager, John, schedules a meeting with the Designer, Lisa, to discuss a new project they will be working on together.

John: Ok Lisa, I’m excited to get rolling on this. We’ll be building a new dashboard for our software that will help users visualize their data more easily. I’ve put together a brief that outlines what I think we need, which I can walk you through.

John shows Lisa a three-page written document that includes two detailed mockups.

Lisa is frustrated. Are we in detailed design (5th triangle) already? What are these mockups? Is she just supposed to make them look pretty? Is that all John thinks she’s capable of? Why hasn’t she touched up her LinkedIn profile more recently? But Lisa takes a deep breath.

Lisa: This is really helpful, thank you. Can you tell me a little bit more about the mockups you’ve included here?

John: Yeah, absolutely. These are some ideas I put together in Figma to try to give you a better sense of what I’m thinking.

Lisa: Got it. So this isn’t carved in stone, it’s not a FACT, it’s just an IDEA?

John: Yep.

Lisa: And what QUESTIONS are you hoping we can answer together? Are you confident in your understanding of our customer’s need, how urgent the need is, and what it’s based in? Or is that still something you want to learn more about?

John: Yeah, I’m pretty confident about that. Really we don’t have a choice, to be honest, because this is the VP’s pet project.

Lisa thinks: Ok, so I need to treat the customer need as a FACT. We’re not exploring, in the 1st triangle, but at least it’s not the 5th!

Lisa: Got it. Then are you confident that this is the best way to solve that need, or is that still a QUESTION that we should work on together?

John: Oh yeah, this probably isn’t the best by any stretch, I just wanted to show you a few IDEAS, like that there is a dashboard that shows progress and highlights issues.

Lisa thinks: “Fantastic, so we’re in the 3rd triangle, ideation, that’s better.”

Lisa: Ok, so we can start our work together capturing the VP’s concept around the customers need, and then explore some other IDEAS for meeting that need in this project. Does that sound right?

John: Perfect, thank you!

Note that if Lisa hadn’t probed and just gone ahead with her first understanding (that she was just supposed to make things look pretty), Lisa and John would have both missed out: Lisa wouldn’t have been able to contribute all she had to offer, John wouldn’t have known what Lisa is capable of, and the end product wouldn’t have been as good.

Going Forward

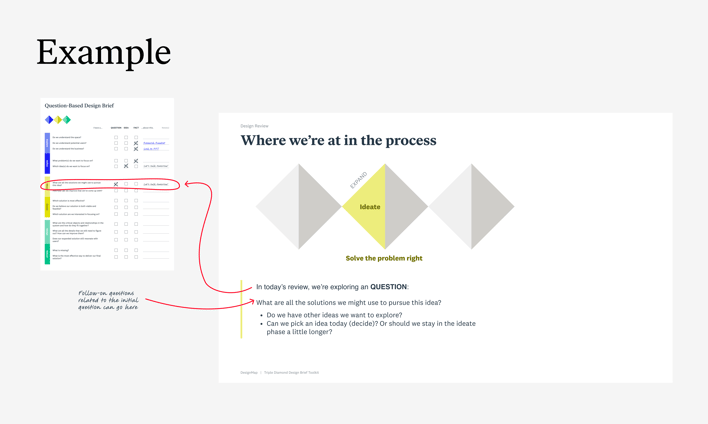

While we imagine that a Head of Design, and every Designer’s, life would be better if every Product Manager used this design brief template (or used some other way to communicate where they are clearly and succinctly), we think it could get even better.

What if this weren’t a one-time, one-way communication, but part of a conversation that went on for the duration of the project? And if, at every step of the way, we could reinforce the breadth of what design can contribute, and maintain clarity about where we are and what’s up next?

Enter a template for Design Conversation Framing (access via Figma).

Here is the idea behind this simple Figma template: add this to to the front of every design deliverable to make sure everyone is clear on what they hope to accomplish today and where they’re going.

You’ll notice that the first question in the template is directly from the Design Brief. This helps reinforce what everyone is thinking about (and at which phase), but also leaves room to discuss more detailed questions for the particular document or review at hand.

At DesignMap, we strive to start every design review with an explanation of what we’re sharing and what kinds of feedback might be useful to get us to the next step. For example, we might say: “These are just some quick sketches of ideas, so we’re interested in feedback on the concepts generally, but aren’t worried about colors or typos, things like that.” Starting with this kind of general framing can help everyone remain aligned and focused as work progresses.

Forget Perfect. Aim for Purposeful Progress.

For PMs reading this, please try to be as open and explicit with your Designers as possible. You will only erode the outcome of your collaboration and, over time, trust with your Designers if you hide things from them to avoid bias (yes, we’ve had this happen, so many times). Or if you try to give the “right” answer instead of the accurate answer to what’s already been decided.

While there’s no “perfect” in the real world, there is progress and I hope that this systematic approach to design briefs allows both Product and Design to unlock all that is possible—if not just for themselves, then for the reason we do any of this in the first place: to solve real problems for real people!

Want to chat about more ways to improve Designer <> Product collaboration? Get in touch to learn how DesignMap works closely with Design and Product to bring out the best in both.

In additional to the DesignMap team, many thanks to Anatoli Olkhovets and Jessie Leiber for reviewing this early and providing feedback and ideas!